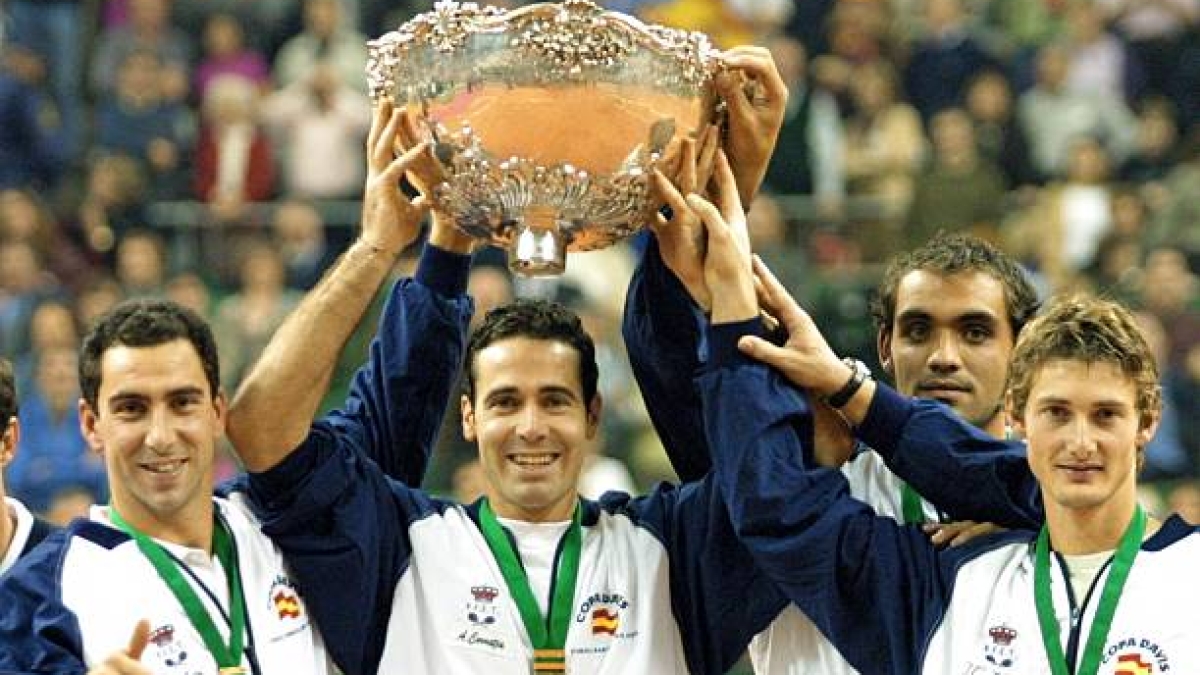

The year 2000 will always be a historic date for Spanish sports. In early December, the Palau Sant Jordi adorned itself to witness one of the most unforgettable moments in our tennis history book: the first Davis Cup in Spain. Many anecdotes and snapshots are remembered from that first Ensaladera, from Juan Carlos Ferrero's passing shot to Hewitt in the deciding point to King Juan Carlos' ""Eh, Patillas."" to Joan Balcells during the trophy presentation. Behind that feat lies a peculiarity, an untold story, somewhat forgotten by many: it originated from a completely unique formula, a bold move by the Spanish Tennis Federation that bore fruit in just a year.

The Spanish Tennis Federation decided to implement the now famous "G4" to lead the Spanish Armada. How? What is a G4? Instead of having a single coach for the Spanish team, the technical team would consist of four coaches, four reference points acting as a single entity. An unprecedented formula that could have led to an ego war but, nevertheless, ended up proving the well-known phrase that unity is strength.

"It was a formula where we integrated three coaches into the team, as if they were part of the regular team: one was Javier Duarte, the coach of Álex (Corretja) and Berasategui, who had trained several players of that era; Josep Perlas, who was the coach of Moyà and Albert Costa, and the third was Jordi Vilaró, the coach of Mantilla. I was, let's say, the link with everyone, as I was the Technical Director of the Spanish Federation and the Director of the CAR of Sant Cugat, traveling to all tournaments before each tie to see how the players were doing and then talking to the rest of the captains to check on everything." Speaking with the marvelous views of the Puente Romano beach in Marbella is Juan Avendaño, a member of a group that was an absolute wellspring of wisdom. The Spanish Federation decided to gather several members of that team in an intimate event to commemorate the victory, leading to an enjoyable conversation with wonderful insights for any tennis enthusiast.

"It is true that it was a formula that seemed odd, but it worked because when you win, everything you do is well done (laughs). The main objective was to win, and it turned out well because everyone, players and coaches, got involved, and it turned out perfectly," says the former national team coach. That selection was overflowing with talent: Juan Carlos Ferrero was close to the top 10 at just 20 years old, Álex Corretja was a well-established top-10 in his prime, Albert Costa was one of the toughest opponents on clay, and Joan Balcells brought magic to the serve and net play that worked so well in doubles.

That was the squad for the Final, which did not include another giant: a Carlos Moyà who had overcome a serious back injury and had not taken part in the previous ties. Josep Perlas, one of the team captains and his coach at that time, was responsible for delivering the news. There was no trace of any conflicts of interest: that council made decisions thinking solely of the ultimate goal, giving Spain its first Ensaladera in history.

THE KEYS TO WHY THIS CRAZINESS WORKED

"It worked because they were four very intelligent people, not only as individuals but emotionally. There was the circumstance that three coaches of players were involved, and there were ties where the coach himself had to tell his player that they weren't going to play. I remember, I have an image of Perlas with Costa, telling him he wasn't going to play, and the reaction... 'Perlitas, Perlitas, don't tell me this,' he said; however, he immediately changed his attitude and started cheering everyone on. Everyone handled it really well," recalls affectionately Joan Balcells, who embraced his role as a doubles specialist with enthusiasm and firmness. Did the same happen when selecting the singles players?

In fact, the tennis players also played a crucial role in this equation. It's not easy to be relegated to a secondary role or even not show up... and have it come from your own coach, as if he, your usual right-hand man, didn't trust you. Everything had a purpose, though, through a path whose undeniable success allowed a certain continuity in the model. The best example of the lack of selfishness and the brotherhood of that generation is described by Álex Corretja, who, despite being the Spanish number one, was not selected to play on the first day of the tie, handing over the baton to Albert Costa who pushed Lleyton Hewitt to his physical limits.

"I think the formula worked because there was a great deal of mutual respect between coaches and players, and above all, there was honesty. If Moyà was not selected for the final because they believed other players should go, he didn't play. On the first day, they told me I wouldn't be playing, Duarte told me that on the plane back to Barcelona from the Lisbon Masters. I was the team's number one, had played in all the ties, but he openly told me that I wasn't going to play on Friday, as they thought on December 10, when we played, I would come very tired to face Rafter on the first day, over five sets, and then tackle the doubles the next day, considered the most challenging match, besides, of course, the possibility of playing the last day in the match against Hewitt once again. It was very complex, and they told me they preferred to keep me fresh for Saturday or Sunday. Joan and I played doubles from time to time, we understood each other incredibly well and brought out the best in each other. What mattered was the team above individualities, which is not always the case. We accepted it, believed in it."

Corretja talks about an "unpopular" decision, one that the public didn't understand at the time. It ended up becoming an example of courage and placing the collective above individualities, sowing the seeds of what would be one of the most memorable generations in Davis Cup history. Avendaño recalls that the journey of this formula didn't stop there.

"It is worth noting that the formula continued. Javier Duarte left, but Perlas stayed and Jordi Arrese joined, becoming a G3: in the following years, three finals were played and two were won. In 2003, we played the final in Australia, which we almost won, and in 2004, we won in Seville against the United States. It was something innovative, something peculiar, but it had continuity and proved successful in sports."

In those wonderful years, everything seemed interconnected: the flag bearer of the 2000 final was a certain Rafael Nadal, the one who would surprise the world by emerging as the prodigy child in the 2004 Sevilla final, the second Ensaladera in our history. In that tie, by the way, Rafa replaced Juan Carlos Ferrero in the lineup... the same Ferrero who had become a hero in the 2000 final, leaving out a Carlos Moyà who, four years later, would secure Spain's second title.

An irreplaceable generation where all circles managed to close. Thanks to an unexpected combination, a formula that not only did not create tensions but also strengthened bonds within a group that was set on achieving what names like Santana or Orantes couldn't. 25 years later, it is a feat deserving to be remembered and applauded, a bastion of happiness from that Davis Cup where being the host or the visitor held immeasurable value. History was made... their way. Long live the 2000 team.

This news is an automatic translation. You can read the original news, 25 años después, España